Although he had directed films before The Lodger, Alfred Hitchcock described this as his true directorial debut. Indeed, watching the film today is complicated by just how much one knows about the director and his personal styles. Many of his signature moves seem to be present here, preternaturally present, elements of an authorial signature that is still to be fully defined in the future: a mysterious and morally ambiguous main character, plot twists and last minute revelations, endangered innocents, eloquent cinematography, a brief appearance by Hitchcock himself (the first of many to come), and of course, blonde women!

The full title of the film defines this as “A Story of the London Fog,” and with this Jack the Ripper plotline the film literally starts with the murder: a close up of a woman’s terrified face screaming straight at the camera, and presumably her killer, her blonde curls glorified in a backlit halo. Combining the abruptness of pure emotion with the humor and irreverence that will soon become a staple of the Hitchcock style, the film explains that this is the seventh victim of a serial killer who seems to select his victims for their golden hair, whether natural or peroxide-enhanced, and follows up with a funny sequence in which spooked dance girls contemplate wearing dark wigs before leaving their dressing room. Mothers try to keep their blonde daughters at home! Professional blondes consider going back to their roots!

The full title of the film defines this as “A Story of the London Fog,” and with this Jack the Ripper plotline the film literally starts with the murder: a close up of a woman’s terrified face screaming straight at the camera, and presumably her killer, her blonde curls glorified in a backlit halo. Combining the abruptness of pure emotion with the humor and irreverence that will soon become a staple of the Hitchcock style, the film explains that this is the seventh victim of a serial killer who seems to select his victims for their golden hair, whether natural or peroxide-enhanced, and follows up with a funny sequence in which spooked dance girls contemplate wearing dark wigs before leaving their dressing room. Mothers try to keep their blonde daughters at home! Professional blondes consider going back to their roots!

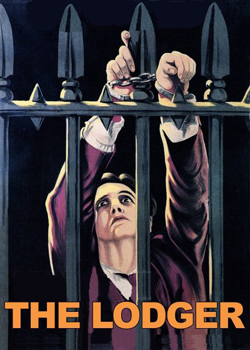

It is into this context of social unease and misty, foggy nights in an expressionist urban landscape that a mysterious man arrives at the doorstep of a family with a room to let. This stranger, of course, begins to keep to himself in a way that becomes increasingly unnerving. Is Jonathan Drew (Ivor Novello) the serial killer on the loose, or is he unjustly suspected because he is a sensitive, slow-moving, intense, silent young man? In contrast to the moody shuffling about of their new lodger, the Bunting family is cheerful and solid. Always interested in social distinctions, Hitchcock contrasts the familial space of the kitchen in the basement with the refined sadness of the lodger and his room.

It is into this context of social unease and misty, foggy nights in an expressionist urban landscape that a mysterious man arrives at the doorstep of a family with a room to let. This stranger, of course, begins to keep to himself in a way that becomes increasingly unnerving. Is Jonathan Drew (Ivor Novello) the serial killer on the loose, or is he unjustly suspected because he is a sensitive, slow-moving, intense, silent young man? In contrast to the moody shuffling about of their new lodger, the Bunting family is cheerful and solid. Always interested in social distinctions, Hitchcock contrasts the familial space of the kitchen in the basement with the refined sadness of the lodger and his room.

The landlady’s daughter, Daisy (June), is soon caught between the easy social manners of her boyfriend Joe (Malcolm Keen), a policeman investigating the murders, and the attractive stranger upstairs whose shy reluctance has its own vampish allure. Annoyed by the interference, Joe begins to suspect that Drew is the killer, and the story takes off from there, with prejudice, jealousy and sexual competition confusing the detective work as bodies continue to pile up.

The film includes a rather daring range of visual experiments, which Hitchcock has explained as a combination of his American training in editing style and his work with German Expressionist directors at UFA in previous years. In the recent digitally restored version, these aesthetic choices shine once more: we have blinking neon signs that advertise the uncannily named play “Golden Curls,” art deco intertitles, expressionist lighting schemes, startling close-ups of Drew’s scarf-covered face, a complex bird’s eye view shot of an oval staircase with the lodger’s hand in perfect focus as he descends, dimly lit and claustrophobic exterior spaces under a streetlight, and the celebrated shot of the family room ceiling with its swaying chandelier evaporating to reveal Drew’s anxiously pacing feet upstairs.

The film includes a rather daring range of visual experiments, which Hitchcock has explained as a combination of his American training in editing style and his work with German Expressionist directors at UFA in previous years. In the recent digitally restored version, these aesthetic choices shine once more: we have blinking neon signs that advertise the uncannily named play “Golden Curls,” art deco intertitles, expressionist lighting schemes, startling close-ups of Drew’s scarf-covered face, a complex bird’s eye view shot of an oval staircase with the lodger’s hand in perfect focus as he descends, dimly lit and claustrophobic exterior spaces under a streetlight, and the celebrated shot of the family room ceiling with its swaying chandelier evaporating to reveal Drew’s anxiously pacing feet upstairs.

There is also a set piece that opens the film and functions as a miniature documentary: it tracks the way a murder becomes news, from the eye witness’s testimony, to the policeman’s investigation, the journalist’s report, and the actual process of printing the newspaper and delivering it in a van through the sleepy city streets. This unexpected procedural segment contributes to the film’s interrogation of the appeal of murder and its presence in public culture. Murder thrills, and murder sells.

Both The Lodger and Fritz Lang’s M a few years later depict the serial killer as a city creature, feeding on the complexity and anonymity of the metropolis and in turn fueling the city’s desire for transgression and gore. Hitchcock identifies social paranoia as part of the problem, as the unknowable city is potentially both sexy and dangerous, and modernity becomes the facilitator, if not the cause, of new social and sexual pathologies. In addition to the sense that the elusive murderer is motivated by a new sexual fascination with blonde hair (a case of textbook cinematic fetishism), as well as a kind of implicit pop-psych misogyny (the killer is dubbed “The Avenger” as if he is avenging on women some kind of wound the women have enacted on him), the film also presents the strange dynamic of crowds, with neighbors and spectators always on the verge of becoming a mob and victimizing the vulnerable. When confronted, Drew presents a touching defense: not only is he not the killer, he is hunting the killer himself in order to avenge the death of his own sister, the first victim.

Both The Lodger and Fritz Lang’s M a few years later depict the serial killer as a city creature, feeding on the complexity and anonymity of the metropolis and in turn fueling the city’s desire for transgression and gore. Hitchcock identifies social paranoia as part of the problem, as the unknowable city is potentially both sexy and dangerous, and modernity becomes the facilitator, if not the cause, of new social and sexual pathologies. In addition to the sense that the elusive murderer is motivated by a new sexual fascination with blonde hair (a case of textbook cinematic fetishism), as well as a kind of implicit pop-psych misogyny (the killer is dubbed “The Avenger” as if he is avenging on women some kind of wound the women have enacted on him), the film also presents the strange dynamic of crowds, with neighbors and spectators always on the verge of becoming a mob and victimizing the vulnerable. When confronted, Drew presents a touching defense: not only is he not the killer, he is hunting the killer himself in order to avenge the death of his own sister, the first victim.

While this explains Drew’s maps of the murders, his suspicious outings, and his collection of newspaper clippings of the serial killer’s exploits (for a while, anyway), it does not protect him from a spontaneous mob about to enact its own vengeance. With Drew handcuffed, hanging from the embankment railing, and under attack by an unruly mob, the last minutes of the film offer one plot twist over another, and articulate a question that Hitchcock fans will find familiar: the killer’s compulsion, the crowd’s bloodthirst, the viewer’s breathless anticipation, are these emotions all that different from each other? Taunting audiences for their own fascination with murder is another classic-to-be move. Hitchcock’s most intimate insights on mass culture are already present in The Lodger, and the movie combines secret thrills and guilty pleasures, the conflicting desire to catch a murderer but also potentially let him get away with it.

![]() Despina Kakoudaki

Despina Kakoudaki

I was invited to write this review of Hitchcock’s first film as part of the PopMatters celebration of the director in June 2010. The version you see here retains the original text with a few added images just for fun. For citation purposes pelase use the original publication of this piece: You can read this and other reviews of his early films in their original location by clicking here.