Perhaps it is the impending film release of The Fault in Our Stars that has occasioned new interest in how the category known as “young adult literature” operates today in the publishing world, the book-to-film world, and the general reading world. The debate has taken many forms this summer, and has intensified after the publication of an article by Ruth Graham in Slate, provocatively titled “Against YA” and proposing that while reading young adult literature is enjoyable for adults it is also kind of embarrassing…

On this topic, I was interviewed by Alicia Lozano from radio station WTOP 103.5, for her article “Making the Case for Young Adult Literature” and our conversation turned up a couple of interesting points. Both of us were intrigued by the list of the 100 Best Young Adult Books as nominated and voted on by the listeners of NPR a couple of years ago. The list includes some familiar titles, such as the Harry Potter series, The Hunger Games, Twilight, The Hobbit, and more recent books like The Fault in Our Stars or The Perks of Being a Wallflower that have found both a young adult and a multi-generational audience and have made the jump from page to screen.

On this topic, I was interviewed by Alicia Lozano from radio station WTOP 103.5, for her article “Making the Case for Young Adult Literature” and our conversation turned up a couple of interesting points. Both of us were intrigued by the list of the 100 Best Young Adult Books as nominated and voted on by the listeners of NPR a couple of years ago. The list includes some familiar titles, such as the Harry Potter series, The Hunger Games, Twilight, The Hobbit, and more recent books like The Fault in Our Stars or The Perks of Being a Wallflower that have found both a young adult and a multi-generational audience and have made the jump from page to screen.

The list also includes books that present the world from a young person’s point of view, but I don’t think we would call them “young adult” because a. the category did not really exist when they were published, and b. they transcend any kind of limit in terms of social and cultural impact, point of view, and literary accomplishment. To Kill a Mockingbird, for example is on this list, as is Fahrenheit 451. Just the fact that these amazing books are on this list should make us pause and consider the importance of this young point of view and what it may make visible, what it may bring into focus, the world-changing potential this not-yet-adult, and not-yet-jadded point of view can have for the way we see the world.

The list also includes books that present the world from a young person’s point of view, but I don’t think we would call them “young adult” because a. the category did not really exist when they were published, and b. they transcend any kind of limit in terms of social and cultural impact, point of view, and literary accomplishment. To Kill a Mockingbird, for example is on this list, as is Fahrenheit 451. Just the fact that these amazing books are on this list should make us pause and consider the importance of this young point of view and what it may make visible, what it may bring into focus, the world-changing potential this not-yet-adult, and not-yet-jadded point of view can have for the way we see the world.

In our conversation I mentioned the great perspective my friend Anne Nesbet brings to her books written for young people, which she describes as “curious books for curious people.” I like the idea that by reading a book for a younger audience an adult can find their own sense of curiosity revitalized or expressed. I also feel that we must remember that no matter how addicted they may be to this young point of view, adults read these books differently, and that all readers, young and old, are dynamic, doing many things at once. It would be very useful to think about what that young point of view can do or show in contemporary culture, because it certainly is not simple or easy to account for.

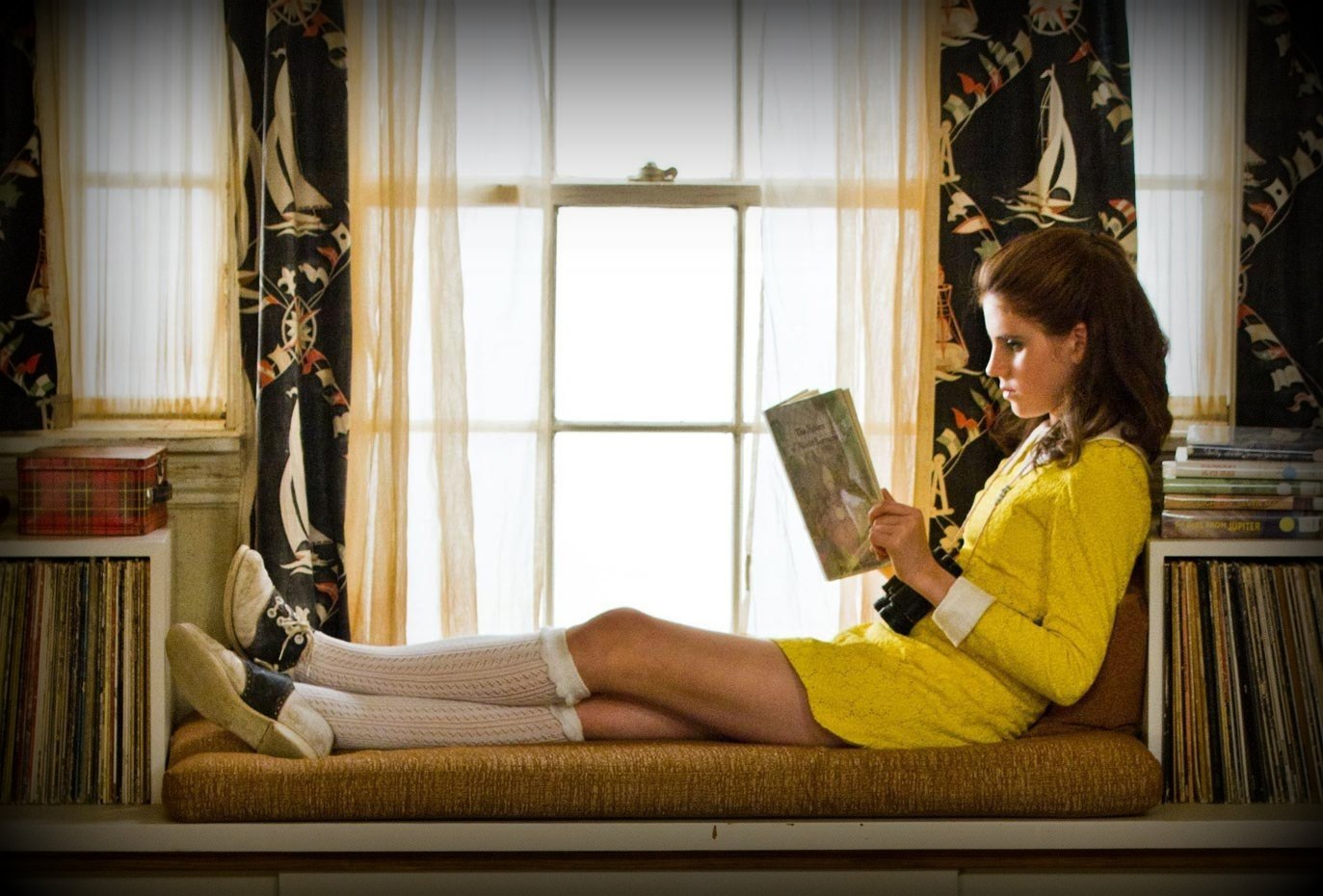

And Moonrise Kingdom? Wes Anderson’s film came up when we were discussing whether cinema has a visual style or a visual approach that would be equivalent to the young adult voice in some of these novels, a simplified, or mannered, or younger kind of image or editing method. I have to think about this more but as of right now I don’t think it does. There are films and TV series made for very young children that have a distinct style, for example Sesame Street developed a whole vocabulary of how to address young viewers, from repeating songs and elements, to having actors and characters break the fourth wall routinely and look straight to the camera, to doing away with narrative conventions and go from one brief element or segment to another without any narrative or conceptual link. But in mainstream narrative cinema, and this would include films made for kids, I would be hard-pressed to find movies that do not share a visual and editing vocabulary, regardless of the presumed age of the primary intended audience. Is there a non-adult visual or editing style in mainstream cinema? I don’t think so, and that is why in the interview I proposed that when a young adult novel is made into a film some of the specificity that the book may have about its point of view and its tone are transformed into a more adult, or more mainstream tone that does not have an age-specific component. How cinema creates its point of view is in itself a huge and complex question, that I won’t go into here.

And Moonrise Kingdom? Wes Anderson’s film came up when we were discussing whether cinema has a visual style or a visual approach that would be equivalent to the young adult voice in some of these novels, a simplified, or mannered, or younger kind of image or editing method. I have to think about this more but as of right now I don’t think it does. There are films and TV series made for very young children that have a distinct style, for example Sesame Street developed a whole vocabulary of how to address young viewers, from repeating songs and elements, to having actors and characters break the fourth wall routinely and look straight to the camera, to doing away with narrative conventions and go from one brief element or segment to another without any narrative or conceptual link. But in mainstream narrative cinema, and this would include films made for kids, I would be hard-pressed to find movies that do not share a visual and editing vocabulary, regardless of the presumed age of the primary intended audience. Is there a non-adult visual or editing style in mainstream cinema? I don’t think so, and that is why in the interview I proposed that when a young adult novel is made into a film some of the specificity that the book may have about its point of view and its tone are transformed into a more adult, or more mainstream tone that does not have an age-specific component. How cinema creates its point of view is in itself a huge and complex question, that I won’t go into here.

In the case of Wes Anderson, what we see in Moonrise Kingdom is a very wise adjustment: Anderson often seeks to present pure feelings of longing or desire in his films, and critics have both admired and criticized this point of view. People sometimes don’t recognize the intensity of the romantic desire in his films because their visual style is so fun, or so hip, or so intensely crafted. We see this in Rushmore, and in the Royal Tenenbaums, and in different degrees in his other films, where a character is suffused by love, first love, impossible love, love in its purest form, untouched by irony or sarcasm, and undaunted, with no sense of self-preservation or holding back. That representation of love seems quirky or a little off with adult characters, even when they are as quirky as the Tenebaums. But with children or teenagers, as we see in Moonrise Kingdom, the sense of longing that would be unbelievable or alienating for contemporary adults (because we are all so knowing, presumably, so aware of our public personas and so invested in being cool) fits perfectly. Removed in time, into a color coded 1970s landscape, removed in space, into a mythic land of campers and essential adults, and removed in age, into young adults who have nothing to lose but their inexperience, the feeling of pure longing belongs perfectly.

In the case of Wes Anderson, what we see in Moonrise Kingdom is a very wise adjustment: Anderson often seeks to present pure feelings of longing or desire in his films, and critics have both admired and criticized this point of view. People sometimes don’t recognize the intensity of the romantic desire in his films because their visual style is so fun, or so hip, or so intensely crafted. We see this in Rushmore, and in the Royal Tenenbaums, and in different degrees in his other films, where a character is suffused by love, first love, impossible love, love in its purest form, untouched by irony or sarcasm, and undaunted, with no sense of self-preservation or holding back. That representation of love seems quirky or a little off with adult characters, even when they are as quirky as the Tenebaums. But with children or teenagers, as we see in Moonrise Kingdom, the sense of longing that would be unbelievable or alienating for contemporary adults (because we are all so knowing, presumably, so aware of our public personas and so invested in being cool) fits perfectly. Removed in time, into a color coded 1970s landscape, removed in space, into a mythic land of campers and essential adults, and removed in age, into young adults who have nothing to lose but their inexperience, the feeling of pure longing belongs perfectly.